This story appeared in The Hopkins Review, Winter 2011

[a pdf of the story is available here: Aerostar]

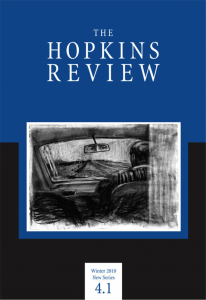

Nando sits in the back seat of the van and watches the planes come down through the rain, one by one, as they light up the mist, and materialize, and roar overhead. He shuts his eyes as they pass and the vibrations rise up through the tires. He is trying to ignore the determined way his parents hold hands across the emergency brake. They’ve just come from one of their marriage counseling meetings, busy working at the marriage, or whatever the hell they do there, he doesn’t want to know. He himself had been blessedly out of their reach, standing in the drizzle covering second base and striking out and generally contributing to the 9-3 loss to Wakefield. And then his parents had picked him up, driven here to Gravelly Point and compelled him to sit and watch the airplanes bear down on Reagan National Airport. Because, he has been told, this is what they used to do back before he was born, back before the airport was named after a president they despised; which is just another way of saying back when they really liked each other, back back back, when when when.

When he thinks about it–and it’s unavoidable, it’s like the persistent odor of some meal already swallowed and forgotten about until the next time you come home and the fumes from cooking it still hang in the air, souring–when he thinks about it Nando figures that they are lonely for something that has petered out. They are nostalgic for a bygone personal era. He feels sorry about this, sorry for them, he really is, but mostly he feels that the burden of this history is not his. For him, there is no before and after, no compare and contrast. He’s just crammed into this Ford Aerostar, his knees jutting up, his head grazing the ceiling. His jock strap, specifically the protective cup that Coach Lynton makes them wear, pinches. Another plane, one he didn’t see coming, passes overhead, the huge insistent hiss of it sliding down as the plane crosses over the van toward the runway.

“Hear that?” says Dad, looking up at the rearview mirror.

Nando makes eye contact with him in the mirror and then looks away. “Nope.”

“I mean the way the sound changed when it passed overhead?” His dad takes advantage of every opportunity to prove that the stuff he learned in junior high has stuck. Yes, yes. The Doppler Effect, blah, blah, blah. Dad forgets that they had this exact same conversation last time they came to Gravelly Point. But Nando is smarter than his dad, a situation that calls for mercy.

“It sounds a little bit disappointed after it passes us,” Mom says. She’d been in the car last time, too, and maybe she even remembers Dad’s little lecture about Doppler, but she allows herself to be pretty vague on such details. Mom has recently announced that she has an artistic temperament. “Don’t you think it sounds disappointed, Nando?”

“That’s the red shift,” Nando says.

“Correct,” Dad confirms. “Sound waves from something traveling away from us.”

“Disappointed,” Mom repeats.

Nando tries not to look at Dad, at Mom, and not even at the plane landing, if he can help it. You can’t let yourself get drawn in to their fascination with the predictable. The plane passes overhead, the wheels go down, it lands. The raindrops gather and roll down the windshield, painting their itsy-bitsy trails. Such petty dramas, again and again and again.

They’re getting divorced. Nando absorbs this from the moment that his parents stop holding hands and turn, in unison, to look at him from between their bucket seats. He knows this even before Dad finishes saying, “There’s something important we need to tell you.”

Not that they go so far as to say the word, divorce, as they go on with it, as all the other words collect and congeal inside the van.

“Moving to my own place,” Dad says.

“For now,” Mom adds.

“That’s right. For now,” Dad agrees.

Right.

Mom and Dad agreed on these talking points in order to spare his feelings.

Why here?

Why not do this in the relative comfort of home? Why is the van better? Compare and contrast. Because . . . because here he can’t escape to his room. Here in the Aerostar Nando must remain folded in position. They are all belted in, frozen in orderly relation to one another, sectioned off in the dark, dented carton of the family. Safe. Of course, any one of these planes could crash. But his parents don’t think there’s a real chance of that, do they? No. Or else why would they park here, right in the path of doom, death and destruction, in the path of an exploding fuselage, of a hideous, ravenous fireball of jet fuel? No. They are responsible parents. Dad, the subcommittee staff director with his House of Representatives ID hanging from a lanyard around his neck, Mom with her big purse with the wallet bursting with coupons and a bent picture of Nando holding Jack the dog, back when both were small and excitable.

Mom reaches back and taps his knee. “You OK, honey?”

“Yep.”

“We wanted to tell you,” she says.

Nando’s cell phone vibrates in his pocket.

“We wanted you to know,” says Dad.

Nando says, “Thanks for the update,” and pulls out his phone. A text message from Dorina. Sorry. That’s all it says. She’s talking about the game. He could call her after dinner. He’s so hungry. His parents stare at him like they’re expecting something. “Can we go now?” he asks, as politely as possible.

“We boring you, son?” Dad says, rotating further and tilting, looking at him hard, bearing down with his Dad look, his alpha, you-disappoint-me look. Everything waits while a plane roars past. “I hate to think what it would take to impress you.”

Apparently Nando is spoiling this for his parents. He’s supposed to react differently, to play his part, the devastated child or something. But what about dinner? Can’t they just eat? “Dinner,” he says. “Dinner would impress me.” He hates it when his parents talk to him like this, their doughy faces full of advice, hates being spoken to as if he were a petulant child. He watches the plane land, studies the reflection of the white and red lights on the wet runway. Why can’t they just get on with it? Get it over with. Stop looking at him, stop steaming up the windows with their versions of things. Divorce? All set! How about some dinner?

“Bet you are hungry,” Mom gives his knee a final pat and withdraws her hand. “He’s just hungry,” she says to Dad in a new tolerant, authoritative tone. Mom smiles firmly at Nando, and from her bright efforts he suspects that she has perhaps been drinking–a quick one, to shake off the marriage counseling? A remedial glass of sherry, standing in the kitchen. As a little boy he used to beg sips of the brown, sweet drink she’d pour for herself every evening to buck herself up. She’d keep the glass beside her on the counter while she took the big knife and reduced a pile of onions and carrots and celery to smithereens.

Nando is glad that she is leading the conversation this way, toward dinner. It has, at last, boiled down to food, their lowest common denominator. Eating is a family project, one they know how to execute, a limited-term plan with its brief satisfactions. Feeding Nando is one of the only pleasures his still parents share. Talking about meals with them is a kindness; it’s the least he can do to help them get through another day together. “Yeah. What’s for dinner?”

Dad starts the ignition, not waiting for Mom’s answer. Mom looks back and winks at him with her left eye, the one that Dad can’t see from his side. Nando pretends not to see her do this even though he knows that Mom’s soft spot for him has something to do with her belief that they agree about Dad. I’m a victim here, Nando thinks, a mere civilian trying to keep my head down during the occupation. There ought to be rules for this under the Geneva Convention, something he needs to study tonight for the test in third period tomorrow.

Although he has a permit and is often allowed to drive the Aerostar–rather than sprawling haplessly in the back with the groceries, umbrellas and trampled MapQuest print-outs–Nando declines his dad’s suggestion that he drive home. Nando prefers to drive only with his father, whose technique involves a pointed silence that Nando enjoys ignoring, allowing him to fantasize about driving alone, or better, with someone else, in a different car, with Dorina, say, in a fully restored Volvo P1800. He would be driving away, his parents would be two tiny shapes receding on the horizon behind him. Driving with Mom leaves him depressed and irritable. The vestigial fealty that allows Nando to play along with her fantasy–that with her pottery class and leather journal and long, complicated earrings, she is unconventional and artistic and modern and furthermore free of the maternal hysterias that afflict the mothers of most of his classmates–is strained past the limit when he drives with her. In the soft, calm voice that she uses only under severe duress, she says, “Careful now,” and she smiles her false smile and says, “Whoops” gaily as he coasts through a stop sign, and then as he swerves around a corner, she balances her fingertips delicately on the dashboard, and closes her eyes, and briefly gives in to the obvious fact that she’s just barely hanging on.

Finally, turkey burgers. Nando has texted Dorina while they cooked. Hits happen. After dinner he’s at his desk, propped over a reasonably engaging chapter in his AP history text book. The theory of war. Mom walks in, saying, “Knock, knock.” In this way Mom pays lip service to whatever privacy he theoretically deserves.

“Whatcha working on there?” She sits on the edge of his bed. She’s had a shower, her wet hair combed and corded over the collar of her frayed yellow bathrobe.

“Looking at a book.” No need to encourage these forays. It’s predictable that around now she wants to escape Dad. It was 9:00 p.m. on the day they finally got around to making a decision. But it wasn’t like in some cheesy old movie where Dad was tossing folded shirts into a suitcase open on the bed while Mom pinned on a hat to go out by herself. No. They were quiet and meticulously polite during dinner. And now, Nando knows in his bones, through the mysterious, defensive bat-like radar that monitored what was going on inside the house, that Dad is in his chair in the family room watching the History Channel. Educational television is Dad’s solace. The soothing, methodical offering of image and narration, like the application of a cool, damp, folded cloth. At least that will be over with, when Dad leaves. At least Mom won’t be coming into Nando’s room because she can’t take one more special on Benjamin Franklin or Viking ship design. He allows himself to hope for at least that much.

Mom’s face is dull with disappointment as she crosses her arms, wrapping up even tighter in her bathrobe. As a small, feverish child Nando had once wrapped himself tightly in that robe while he waited for her to come back from the drug store with amoxicillin for his ear infection. He can remember waiting on his parents’ big bed, swaddled in the robe, listening for the wheels in the gravel driveway and inhaling his mother’s peppery scent. He owes her something now, he has to say something more now, to kick something her way.

“Yeah, so this guy here says war is just a continuation of policy.”

“Interesting.” Mom leans forward, grateful. “You mean, like Rumsfeld.”

“Uh, right.”

“The problem is, people believe in war when they ought to believe in peace.”

“Yeah. I probably just need to read some more.” He thumps his textbook with a flick of his thumb, the way his mother checks whether a cantaloupe is ripe.

“Sure.” She comes over to him, puts a hand on his head as if he was still her tow-headed fledgling.

“You OK?”

“Yep. Studying here.” Nando focuses steadily on the cover of the book, The Earth and Its People. “Big test tomorrow.”

“I’m sorry about me and Dad, Nando.”

“Yep. It’s too bad.” Her hand remains on his head. Leave. Leave.

“Our little boat is yare,” she says dreamily, tossing his hair briefly, mercifully briefly. “It is rocked but still it floats.” When that is finally over, she steps toward the door and then stops, one hand on the knob, one hand holding the big floppy collar of her bathrobe together at her neck. “It’ll be better for everyone,” she says. “Don’t you think?”

“Right.”

“So, you’re OK?”

“Yes, for the seventeenth time, yes.” So far, the divorce is like an excruciatingly dull marriage. Mom pesters and ignores him and is never, ever going to leave him alone. “Yes. What the fuck! Yes, yes, yes.” This drives her away, at last. He checks his phone but Dorina has not responded.

In eighteen months he will be in college, preferably far, far away. Or in Australia or Canada or wherever. Between now and then, between here and there, is only so much left to log, only so many tests, and games, and parties. Only so many more times with Dorina in the back of the Aerostar. One more birthday, a little more lifeguarding for beer money, high over the pool, behind his sunglasses, the kids splashing below in their water wings. Then he can go. He’s not stuck with Dad the way Mom is. He’s not stuck with any of it.

Nando aces his history test. Coach Lynton, whose one teaching responsibility is AP World History, hands it back to him the following Tuesday with “100%” in red pencil on the top right-hand corner. Nando always makes good grades. Every good grade is another layer of protection, a little more fat to sustain his flight to some future TBD. He attacks school as if it were an unworthy opponent. Most of his teachers, he knows, don’t much like him. Teachers are drones, stuck forever in the tiny world of bubble tests and hall passes and fire drills. The problem, Nando knows, is that they detect his contempt.

“Thanks, Coach,” he says earnestly. Nando is hoping that Coach will let him pitch in tonight’s game against Westfield. He plays first base but has been put on the mound in two games this season, and when he got the save in the Yorktown game, the coach said he’d let Nando start before the season was over.

Coach Lynton works his way down the aisle with his armload of tests. A long time ago, maybe ten years back, he quit his job at some big law firm downtown to “answer a calling,” or so claimed the yellowing Washington Post story featuring “career changers” that he himself posted on the bulletin board for back-to-school night. He had to prove that he was no dumb baseball coach but a former minor leaguer and a graduate of UVA law school. But mostly everybody laughs about how crappy he looks now, compared to the picture in the Post, which was back before his wife left him, back before he got so bald and bagged out. Once, last summer, Nando had driven past the school with his father and noticed Coach Lynton pushing a small lawnmower across the outfield. Nando had rolled down his window and heard the gloomy rasp of the mower’s engine as the coach made his infinitesimal progress through the grass.

Nando goes early to the field, hoping, through this display of eagerness, to shore up Coach’s inclination to put him on the mound. Nando likes the baseball field; he likes all baseball fields. Wherever he flies–to his grandmother’s or cousin’s–he looks down and finds baseball diamonds in every twinkling town, the shape branded on every landscape. He likes their geometry, the bright white lines angling from home out into the grass, creating a wedge that opens up from the measured, packed infield to the open infinity of the outfield. He loves the pitcher’s mound, the gentle elevation of the earthen dais in the center of it all. He loves standing on it, peering down at the batter, then the soft step backwards, a raise of the knee, and a quick lunge toward home plate. He follows the soft fade of his pitch, hears the clink of the bat, and watches the ball coming back the other way, studying the angles, the trajectory. He loves to catch the hard, smooth ball with its red seams stitched in the essential horseshoe pattern. And then another pitch.

Nando hopes Dorina doesn’t come to the game. She makes him unsure of himself, a feeling he can’t afford. He hopes his parents don’t come, either. In the week since they told him that Dad is moving out, they’ve been watching him on the sly. On Sunday, at the kitchen table, eating pancakes his mother made him after he got up at two in the afternoon, sitting between his parents as they pretended to read their separate sections of the paper, darting their eyes at him when they thought he wouldn’t notice, it got so bad that he pushed back from the table, grabbed his plate, tucked the bottle of Aunt Jemima under his arm, and tromped back to his room to eat in actual peace.

Dad, it turns out, has already sublet a place from some congressman who just resigned after an intern he’d been sleeping with posted his voice mail message on her blog. He’s been discreetly packing his car and taking loads of stuff over every day on the way to work. Nando discovered this over the weekend when he was working on a paper and couldn’t find the thesaurus. Dad admitted, when he came back in from walking Jack, that he’d taken it, and that it was over at his new place, his temporary, “time-out” place. Apparently he was going to be there long enough to want the thesaurus. “You can always use the internet,” Dad said, shoving his hands stupidly in his windbreaker pockets. But it was true. Is true. There’s a lot of stuff that Nando can do without just fine.

The school parking lot, which lies between the school and the playing fields, is only half full now, just the cars of some teachers and the drama club and some other dregs inside rounding out their extracurriculars or serving detention. Soon the baseball parents will arrive with their folding chairs and video cameras. If Nando’s lucky, D-boy’s dad will come lubed up with gin and tonics and stand by the fence and yell at them. “For the love of God! Catch the damn ball!” The other parents get all torqued about it but Coach just shrugs. It’s a beautiful thing.

There’s Dad, now, down the third base line, resting his arms on top of the chain link fence. Not waving shows a rare, manly restraint that Nando appreciates. The team is warming up, throwing some balls around. No sign of Mom. From now on they’ll probably take turns. It’s going to be either, or. It’s going to double the time he has to spend with them, whatever that is, forever.

Dad keeps talking about college ball, but Nando knows he’s not that good, not for a scholarship or for division one. Nando told him he wants to go to a D3 school, where he’d play more ball and get an education, an angle he knows makes him appear “focused” and “goal-oriented” and thus placates his father. His dad has started an accordion file in the family room: Oberlin, Reed, Davidson, Occidental, FAFSA, NCAA. Sometimes he thinks he loves baseball just because it staves off everything that’s not baseball.

Nando’s starting. Yes. Coach Lynton sends him to warm up with Kevin, the back-up catcher. “Just keep it down,” Coach says, scratching the side of his neck. “Throw strikes. OK?” Running out on the field, everyone takes their positions. Nando gets to trot up to the mound. A clear, fine moment before it all begins. In the third inning he walks the bases loaded, bringing Westfield’s lead-off hitter, who had hit a triple to start the game, back to the plate. Every pitch is a new possibility; you have to make yourself believe that. But the hitter clocks a fastball, and it goes out, far over Nando’s head and far out of D-boy’s reach in center field. That’s it. Coach pulls him, calling time and striding to the mound with his head down, the bill of his cap hiding his eyes. When he gets there and accepts the ball, he says, “OK. Good job” to Nando in his small, numb way. Nando sits in the dugout for the rest of the game, down at the far end of the bench, a bag of ice draped over his shoulder. Holding it gives him something to do, shoving it into position and rearranging it. He ought to feel angry with himself, and with the bad signals and the bad calls and the bad luck. But he doesn’t. He’s not angry at all. He holds the ice with his left hand, the palm getting clammy. He feels a bug, or is it a drop of sweat, moving down the back of his right calf. D-boy’s dad should rant and rave and curse him. Then he’ll laugh and everyone else will laugh, too. But there is nothing but the lights and the scoreboard and the vast blank disappointed face of his father somewhere nearby.

In the fifth inning the ump invokes the slaughter rule and Westfield wins 12-1. Then a desultory talk from Coach Lynton–he didn’t yell at Nando, only at the good players–and Nando and the rest run the required dashes in the outfield. Then they swarm the infield, pulling up bases, and Nando and D-Boy drag a chain mat across the infield, raking up a puff of red dust that quickly settles back to the ground.

Dad stands on the other side of the fence, waiting by the aluminum risers, watching, twirling his keys on a finger. Finally, Nando collects his gear from the dugout and then, as he passes him on the way to retrieve his backpack, he mutters, “Meet you at the van.”

Dad takes him to eat at a Hunan Kitchen near their house. Mom has not made dinner. They’re on their own.

He always begins with a word of consolation, and now he leans in, closer to Nando. “Hits happen.” Had Dad gotten that from him or the other way around? There’s always more. The waiter comes and sets down two large plastic glasses of water and two straws wrapped in thin, sterile paper. “You notice the Georgetown coach was there?” Dad says. “Tough luck.”

“I don’t care about Georgetown,” Nando says. Dad picks up a straw and slowly, methodically peels off the paper. We are here to talk, to have a conversation, Nando thinks, and not about Georgetown. If he’s lucky he’ll get his food and start in on it and eat it fast before Dad gets too far. What do they want from him? It’s like they think there’s more to say and they expect him to say it. Nando looks at his paper placemat, which describes the personalities in the Chinese zodiac. “Roosters are losers,” he reads, “and though they give the outward impression of being adventurous they are timid.”

Dad squints at his placemat. “Loners. Roosters are loners, it says.”

The waiter serves their General Tso’s chicken and moo shu pork, refills their water.

“I thought we might talk about things. About what’s going on. I thought I might see if you have any follow-up questions.” He unfolds a pancake on his plate as he talks, and paints on a dark smear of plum sauce with the back of a miniature spoon.

So this is how it will be from now on. The two of them out in the world, awkwardly facing each other across the closed geometry of some neutral venue. This is Dad’s choice. Maybe it is meant to make Nando feel mature, but it doesn’t. It is like the night, eight years ago, when Dad took Nando to Baskin-Robbins and said he wanted to have a conversation, which sounded exotic and grown-up. Nando asked for a cone of pistachio ice cream and they sat at a small round table outside while Dad explained that Poppi, Nando’s mother’s father, whom they saw in Cleveland every other Christmas and who sent him a brand new twenty dollar bill for his birthday, had suddenly died. Be nice to your mother, Dad had said, as Nando sucked the ice cream through a hole he’d bitten in the bottom of the cone, sucking so hard his cheeks hurt. Pistachio wasn’t nearly as good as he’d hoped it would be. They could bring Mom some ice cream, Nando said, thinking what he could do to be nice, they could pick out a flavor for her, something other than pistachio. Would that be nice, he’d asked, but Dad hadn’t said anything, just reached across and dabbed his face with a napkin.

“It’s not my business,” Nando says. But Dad keeps talking, and Nando feels sorry for him. Dad deserves mercy, if nothing more, and so he lets Dad say whatever he’s saying, while Nando spoons up a huge serving of chicken onto a mound of rice. He eats. He has replaced his baseball cap with a striped watch cap. In place of his cleats he wears rubber shower sandals. He nods and pretends to listen. Nando doesn’t need the details. Dad and Mom are breaking up for good, but neither of them has the nerve to tell him flat out. What Dad does say is, “Be nice to your Mom.”

“I’m always nice to Mom.” Didn’t Dad see that? He should put his Dad out of his misery here, tell him he knows. This is not temporary. It shouldn’t be. It’s cruel, this way. “I’m the one who’s always nice to Mom, OK?”

Dad nods.

“I’m serious. Let’s all be nice to Mom.”

Dad glares at him, the alpha look. “We are all considerate of your mother,” he says, slowly.

“Right.” Nando smells his own his own acrid stench, the smell of locker rooms, of moldering socks and jock straps and stale farts, that is rising and overpowering the smell of the cheap, greasy food piled on the table. It’s so sharp and strong that he pities his Dad. “Get on with it.”

“Nando–”

“Be done with it.”

“Son–”

It goes on like this indefinitely. Dad receding, never quite gone, reaching for his wallet, disappointed, paying the waiter, jiggling the keys, gassing up the old Aerostar the time, five years later, when Mom lets Nando use it to move into the apartment he rented in New York with two friends from college. Nando had wanted to drive up and move in without the embarrassment of parents. But his father had called and asked if he could come along. “I thought we could talk,” he’d said, his voice breaking in and out on Nando’s cell phone. That’s nice, his mother had said, gliding a pan of lasagna into the oven.

Waiting in the driver’s seat, Nando sees him in the rear view mirror, studying the numbers on the pump as they turn, his thin hair ruffling in the wind, one hand gripping the nozzle, the other clenched for warmth in his jacket pocket. Happy.